Negotiation [portrait]

Store Review (0)PRESENTED BY : Alexander Opper

| Frame | None |

|---|---|

| Edition Size | 7 |

| Medium | Photography (Epson Ultrachrome pigment inks on Felix Schoeller True Fibre Matt paper, 200gsm.) |

| Height | 35.80 cm |

| Width | 26.50 cm |

| Artwork Height | 34 |

| Artwork Width | 25.3 |

| Artist | Alexander Opper |

| Year | 2023 |

NOTE: I'm a sole practitioner and, hence, not a VAT-registered vendor.

Each photo: Paper size: 26.5 x 35.8 cm; Image size: 25.3 x 34 cm.

BACKGROUND:

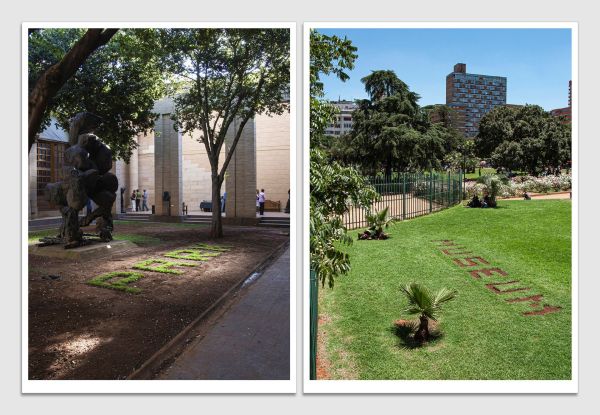

Negotiation, the original work, realised in 2010, consisted of a time-based site-specific intervention. The intervention made use of equal volumes of repositioned soil and lawn from the main courtyard of the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG) and Joubert Park respectively.

The original work is evidenced, here (2023) in an editioned photographic diptych, shown for the first time at ‘Sunny Side Up’, the summer group show that opened at Graham Contemporary Gallery on Thursday 26th January 2023.

Below follows an edited and extended version of the text released on the occasion of the intervention at the JAG, in 2010:

The site-specific intervention Negotiation (2010) forms part of a large and ongoing body of work (1) that considers underlying power relationships implicit in spatial configurations in various institutional and urban contexts. In my artistic practice, Negotiation and other site-specific works have developed from moving away from my original position of ‘making’, or ‘doing’, architecture, towards its ‘unmaking’ and ‘undoing’. Through an interrogative process I aim, in my works and my writings, for a re-versing and extension of the staid and self-assured discipline of architecture.

Negotiation addressed the strangely dysfunctional relationship between the institution of the museum and the institution of the park. It considers the space of the park, adjacent to the museum, as a different and more dynamic form of what we conventionally understand the ‘archive’ to be. It imagines the park as a produced and lived archive, a counter to the calculated accumulation constituting the mausoleum-like, inanimate archive of the JAG’s vast collection of artworks.

For this site-specific intervention, parts of the park and museum surface were physically cut, lifted and moved. These park and museum excisions were then reciprocally re-placed and dis-placed into the temporarily voided surfaces of their adjacent typology, respectively: a precise square meterage of the park’s lawn was cut-and-pasted into the museum’s central courtyard; the same square meterage of the museum courtyard was cut out and transplanted into the park. This archaeological swap opened, and continues to open up, questions about the passed-down definitions, meanings and values of prescriptive and predominantly western typologies – such as ‘museum’ and ‘park’ – in the context of Johannesburg. The transplanting of one ‘accepted’ spatial construct into another results not only in a reversal, but also a typological doubling and re-naming of the two public ‘bodies’ under consideration: the park ‘becomes’ – at least momentarily – the museum, and the museum the park.

The intervention involved the literal cutting of the word 'museum' out of the grassy surface of the park, in a gridded, pixel-like font. Similarly the word 'park' was sliced out of the museum’s central courtyard in square-shaped segments. Each cutting manoeuvre resulted in transplantable blocks of exactly the same lifted quantities of grass (park lawn) and soil (museum courtyard). Once extracted these blocks were then re-cast into their new positions: the soil from the museum courtyard was transferred to the park and was used to spell out the word 'museum'; the excavated segments of park lawn were used to fill up the void that had resulted from cutting out the word 'park' in the museum’s courtyard.

I predicted that, over the course of the ‘Time’s Arrow’ exhibition, the soil transferred from the museum courtyard into the park would become over-grown by the park lawn – in other words, that the transferred piece of the museum would be absorbed and essentially ‘overwritten’ by the park. Similarly, I envisioned that the imported lawn spelling the word 'park' in the museum courtyard would likely be refused by its new host, in the context of the museum’s mostly shaded courtyard.

For this exercise, the shifted and grafted park and museum matter became – to borrow a term from Robert Smithson – ‘non-sites’ (2) removed, reconfigured, re-membered and ultimately rejected by their new contexts. The entropic displacement of the matter comprising the respective ‘type-cast’ surfaces resulted in a simultaneous yet precarious balance of difference and sameness. The uncanny condition of tension the intervention managed to set up was heightened by the presence of the contested palisade fence, which acted – and still acts – as an awkward hindrance between ‘park’ and ‘museum’.

The way these two public spaces tended to, and continue to, marginalise each other and their respective user groups was temporarily undermined by the guerrilla-like nature of this exercise of dual ex-scription, resulting in the forced slippage of the two surfaces into one. The displacement of the park and museum respectively was carried out to prompt hopeful reimaginings. The intervention used notions of mirroring, doubling, mimicking, rescripting and re-inscription to prompt new possibilities of value exchange and hybridisation. It flagged the need for radical thought around the realisation of constructive institutional redefinition, dismantling – even possible dissolution – towards new, coproduced and anti-typological fora of public and cultural exchange.

In conclusion, the above process of the ‘undoing’ of physical fabric was an attempt to understand but, more importantly, to interrogate and undermine what is already there, and highlight the stasis that exists as a result of a lack of fluid and dynamic exchange between what are, in fact, two potentially excellent public (both can be visited freely and are free of charge) resources. The time-based (un)becoming of these two complex publics provoked the question of why and how we measure and ascribe value to these spaces in their current forms: the crypt-like, fortified museum and its largely hidden archive, and the visible and unpredictable lived ‘archive’ of the park. The intervention’s deforming and transforming moves attempted to raise issues and encourage critical debate around the generally unquestioned conventions that govern a hierarchical disposition of spaces within buildings and cities, the power relationships that exist between architectural and urban spaces, and the absolutist morphologies of architecture at large.

(1) Negotiation develops certain of Robert Smithson’s notions, especially regarding his indoor works constituting matter from outdoor sites, into a potentially endlessly recurring entropic transferral of an outside into an inside (park-museum-park… ad infinitum).

(2) For details of site-specific works leading up to the making of Negotiation, see the paper Undoing Architecture (presented by the artist at the On Making colloquium, at the University of Johannesburg’s Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture, in October of 2009): https://www.academia.edu/21407615/_Undoing_Architecture_2010_double_blind_peer_reviewed_paper_published_in_conference_proceedings_book_